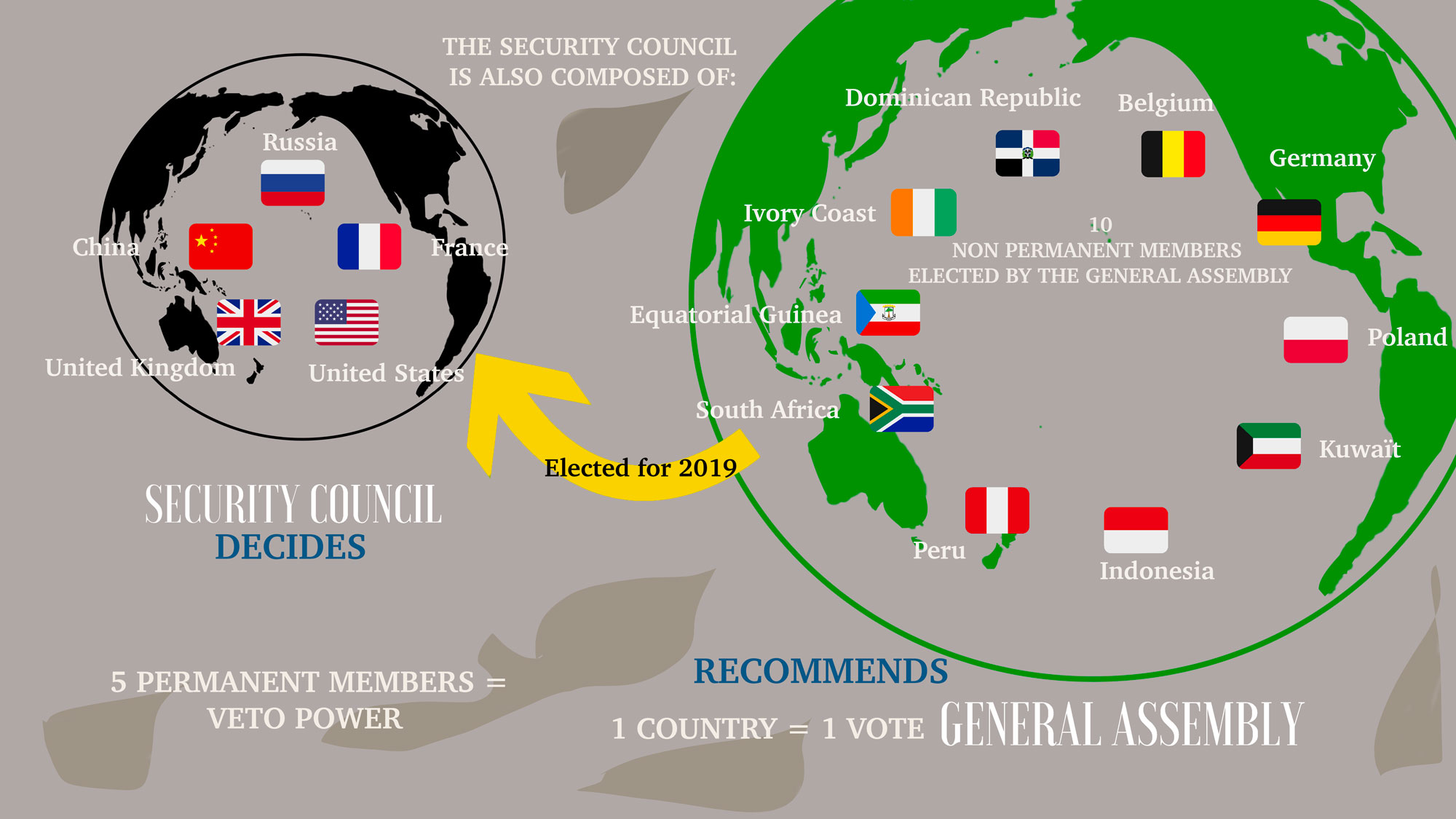

On 28 November, Olaf Scholz, the German minister of finance, requested that the French seat be turned into a joint EU seat at the UN Security Council. France firmly disagreed, arguing this was the exact opposite of the strategy Germany and France themselves have followed for some time. These two neighbours are actively seeking to extend the Council to Germany, as well as Japan, Brazil, India and another African country yet to be determined. Veto power always lies at the heart of these discussions. Many States seem to be bringing a knife to a gunfight when it comes to negotiating at the United Nations round table. Another pertinent analogy is with the combat between David and Goliath. Facing Goliath, David’s slingshot appears inadequate. At first sight, veto power doesn’t appear likely to bolster international cooperation. Quite the opposite, it can be seen as proof of inequalities among nations, and is sometimes used as a means of pressure. Proposals have been made about involving new emerging countries in the UN Security Council, where China, France, Russia, the UK and the US hold seats. But can there be effective international cooperation without veto power? Antonin Macé and Rafael Treibich argue that there can.

At the winner’s round table

Following the Second World War, with the ensuing international geopolitical shuffles, a new supranational cooperative institution was created, the United Nations Organization. The United States and the Soviet Union (USSR), the winners of the war, were the two global superpowers running international relations during the second half of the 20th century. After the defeat of Germany, the Allies divided the country and each governed part of it. Japan, devastated by nuclear war, capitulated and the land of the rising sun was placed under the guardianship of the United States. Finally, the United Kingdom and France, still colonial powers, were both faced with rebuilding their war-ravaged countries. The seeds of this organization, intended to replace the former League of Nations, were sown during the Second World War. After the failure of the League of Nations, initially implemented as a means of ensuring peace and avoiding the repetition of such bloodshed, the new organization wanted to encompass the whole world. To this end, the issue was finding mechanisms that would encourage all countries to participate.

Arm wrestling or cooperation?

Antonin Macé and Rafael Treibich use an optimal decision rule called “self-enforcing” existing within the international institution. This method seeks to ensure the adherence and the respect of all towards the institutions. Every nation faces a trade-off between the gains obtained from adherence and those obtained from isolation. What are the mechanisms – veto power, overweighting – that should be set up to encourage States with different interests to cooperate?

Game rules

In their model, States carry different weights and are willing to cooperate through a supranational instance in charge of decision-making under a given rule. Each nation decides unilaterally to collaborate, according to its best interests. This pattern is compared with a standard scale, called by the authors the “efficient rule”, similar to a control sample. This rule imagines the best possible world, one that maximises collective well-being: states are committed to respecting the international agreement. The model yields typical states’ responses: depending on their weight and positions, they have more or less power to put pressure on their partners. What the pattern reveals is that self-enforcing rules are “carrots” used to get States to cooperate. But some of the donkeys are recalcitrant.

Different strategies for different players

To fulfill the international commitment, each State has to implement the decisions previously taken. How can States be prodded into action when the reference point – where everything is for the best in the best of all possible worlds – is not working? In a qualified majority vote, States predicting that a decision will be to their disadvantage may prefer to go it alone. Whether or not they respect the agreement is closely linked to their negotiation power. Increasing their impact on decision-making provides an efficient incentive for commitment. As an example, the representation thresholds can guarantee sufficient influence for the smaller member states. In the United States, the electoral college that votes for the President grants each federated State a minimum of two representatives. But what about tough-guy States, those for whom the carrot is not enough? This is where the veto right comes in. To sum up, there are three groups of States. The first is composed of countries that will not implement a decision if it contravenes their interests. To encourage their cooperation, the veto right allows them to block all measures they disagree with. Permanent members of the United Nations Security Council use this right. The second group is composed of nations that might not respect the agreement. They are therefore granted a more significant impact on decision-making than in the reference point situation, with more influence in the vote. The third group are states that will respect the agreement whatever happens, which means they follow the reference point.

The distribution of cards and its consequences for the rules of the game

Differences between countries made veto rights or overweighting voting procedures necessary. These rights took into account the balance of power existing at the time of the international institution’s creation, and were needed to ensure the establishment of institutions. For instance, when the UN was created, the right of veto was a sine qua non condition for the participation of the Second World War winners: the United States, the USSR, the United Kingdom, France and China. They used their position as a lever, dictating their conditions, to ratify the UN Charter in 1945. Had these conditions not been accepted, no agreement would have been possible. At the same time, the right of veto underlined their new place in the international community. Behind this paper lies the question of multilateralism and how it becomes efficient and sustainable. What is the best way to convince States to implement an optimal decision for all, but which may be against their interests? Their participation in the international coalition is not sufficient to ensure that concrete actions are taken. Many international cooperative institutions have emerged since the beginning of the 21st century. Some of them are non-binding, such as the COP, a cooperative body originating from the UN Climate Change Conference. In these organizations, participation and ratification do not compel States to enforce resolutions. By contrast, the binding rule exerts pressure on States to implement by all means the measures decided. These norms hold sway at the UN. Perhaps the COP could do with some “carrots”, to become binding.Florian GuibelinComputer graphics : Claire Lapique© Photo cc_Jason Leung_Unsplash