Is the program “Who wants to Be a Millionaire?” the only way out of poverty? Apparently so, at least for Indian Jamal Malik in the film “Slumdog Millionaire”. Yet even that wasn’t enough: although he astonished everyone by being able to answer every question and winning the last 20 000-rupee question, he was accused of cheating. Are poor people condemned to stay poor? The question doesn’t just concern inequalities, but also social mobility: is changing one’s destiny possible for everyone?

For the past few decades, indexes and indicators have focused on inequalities between countries and regions. Sometimes neglected, mobility in income and social status can shed light on issues like poverty, equal opportunities or social reproduction.

Are inequalities always harmful? This question has crossed multiple disciplines, like economics. Mobility may offer the answer. If individuals can climb the social ladder rapidly and without pain, the answer might be no. Those at the bottom of the ladder would take turns with those at the top. Thomas Piketty himself said “Greater mobility is often mentioned as a reason to believe that increasing inequality is not that important”1. Rawls’ egalitarian theory is relevant to this, replacing equality of outcomes by equality of opportunities. There is no advantage to achieving perfect outcome equality so long as initial circumstances are fair and equal for every individual, who will be judged on worth and effort.

Inequality and low social mobility: inherent?

Equal opportunities are linked to mobility. The concept of intergenerational income mobility is based on the degree to which a child's social and economic opportunities depend on his parents' income or social status. But this mobility can also be compared between different periods in a person’s life, from an intragenerational point of view. How many people could rise to the top like the character from a poor farming family who became a millionaire, “The Great Gatsby”? In each country, the answer would be quite different. But at least one thing remains constant, as illustrated by the Great Gatsby Curve. More inequality is associated with less mobility across generations.

It seems harder to climb the ladder when the rungs are farther apart. In the United States, this challenges the symbol of the self-made man. Actually, the American dream is not easy to realize: a 2014 survey by Chetty, Hendren, Kline and Saez2 claims that social mobility remained unchanged from 1970 to 1990. The new generation had the same opportunities to reach higher incomes, while the gap between incomes increased. Income inequalities do not foster mobility, they are spanners in the works for the poorest people.

What are we measuring?

When it comes to international comparisons, inequalities are one of the main factors assessed, mostly through Gini or Theil indicators. These indexes measure the distance between the existing situation in a country and the perfect equality case. Few evaluations concern intergenerational mobility and those that exist are patchy, non-harmonized or involve false assumptions.

Cowell and Flachaire show that the intergenerational mobility index most commonly used can be blind to certain downward and upward movements and that results vary widely. To overcome these limitations, the authors create a new indicator, establishing basic principles.

The measure takes into account different types of mobility. It distinguishes income mobility from rank mobility, which concerns social position. Comparing the two is important: if all individuals increase their income without changing their position, increased income mobility will leave social mobility unchanged.

Which mobility are we talking about?

The authors observe China at the turn of the millennium and reach the same conclusion. At the beginning of the 2000s, China was enjoying rapid growth but the impacts on mobility are unclear. In their article, Cowell and Flachaire show that there was increased upward income mobility, meaning that some people were achieving a higher income than before 2000. At the same time, rank mobility remained stable. Their result confirms the great increase in inequalities observed in China. The individuals whose income increased were those born into well-off families. The Great Gatsby curve is confirmed: great inequalities are linked to low social mobility.

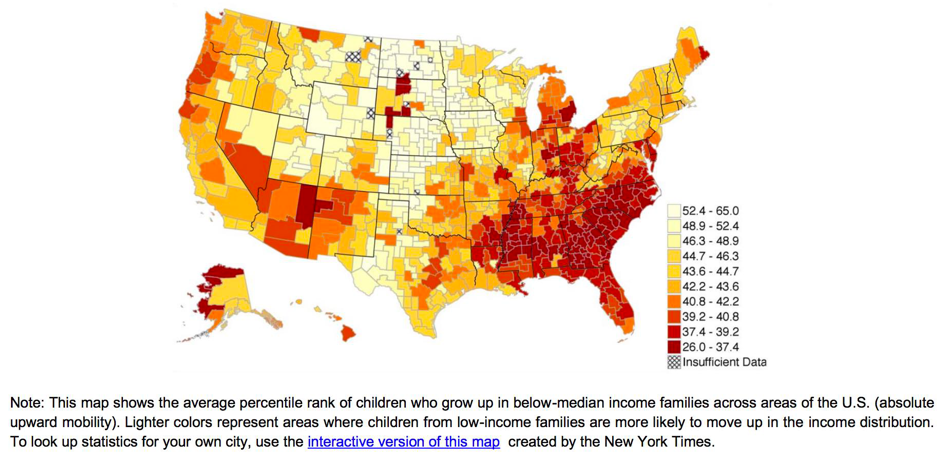

In China, distinguishing the different kinds of mobility makes perfect sense. It is not possible to use the inequality index to assess flows within generation or periods. To further refine assessment, the geographical dimension is useful. It shows the discrepancies existing within a country or even a region where rank and income mobility are concerned. For example, the Middle Kingdom can be divided neatly into rural and urban. The United States is another example of a diversified mosaic, with some States embodying the American Dream and others where there is little chance of escaping the poverty trap.

Geography is not the only variable that counts in the mobility assessment. Cowell and Flachaire’s index can be broken down to identify, for instance, the proportion of wealthy individuals or young people in the final result. Above all, it can be used to explain how upward and downward mobility affects flows. By studying a distance – in terms of income or rank- between two given periods, the mobility index encompasses the inequality index. This latter is a particular case in which the survey period is compared to perfect equality.

Social mobility has not yet been addressed by systematic global measures. However, this would help public decision-makers by providing an accurate picture of the existing opportunities for individuals facing persistent inequalities. It is to fill this gap that economists Cowell and Flachaire created an indicator of mobility.

Emmanuel Flachaire et Claire Lapique

© Photos Souradeep Rakshit, Chang Duong on Unsplash et Flickr

Reference : Measuring mobility, Frank A. Cowell and Emmanuel Flachaire, Quantitative Economics, Volume 9, Issue 2, pp. 865-901, 2018

- 1. "Greater mobility is often mentioned as a reason to believe that increasing inequality is not that important." (Piketty, 2014, The Capital in the Twenty-First Century p.299)

- 2. Chetty, Hendren, Kline and Saez (2014), Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States, Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Chetty, Hendren, Kline and Saez (2014b), Is the United States still a land of opportunity? Recent trends in intergenerational mobility, American Economic.