Julieta Peveri, Marc Sangnier, 2023, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Volume 214(C).

»

We explore whether women’s propensity to remain in politics

after a win or a loss differs from that of their male counterparts.

RESEARCH QUESTION

As of today, women serve as heads of state in only 31 countries. Only 26.5% of members of parliament are women, and less than one in four cabinet members. Therefore, we are far from achieving gender equality among policymakers.

Addressing this gender disparity is important for two compelling reasons. First, it aligns with a normative objective that should characterize modern societies. Second, evidence suggests that women are more inclined than men to make decisions responsive to the needs and concerns of female citizens. Hence, it is vital to achieve equal representation of genders among officeholders to ensure a fair reflection of society’s preferences.

To succeed in closing this gender gap, it is crucial to understand the drivers of women’s low presence in politics. Among the potential explanations, women’s reluctance to run for office and discrimination by voters or political parties against female candidates have been active topics of research. We focus instead on an alternative explanation: gender differences vis-à-vis persistence in political competition. We explore whether women’s propensity to remain in politics after a win or a loss differs from that of their male counterparts. This hypothesis is supported by a substantial body of literature in behavioural economics, revealing that women are less comfortable than men in competitive environments and are more likely to shy away from such contexts.

Our paper focuses on candidates who ran for mayor in France in 2008 and 2014. To investigate this issue thoroughly, merely comparing all municipalities led by a woman with those led by a male mayor would not suffice. Such an approach would fail to isolate the gender of the mayor from the political preferences and gender norms of the municipalities electing a woman. Instead, we concentrate on gender-mixed close elections—those in which a female (male) candidate barely beat a male (female) candidate. The rationale behind this strategy is that in elections defined by a tiny margin, the outcome of the election (in this case, the fact that the elected mayor is a woman or a man) is as good as random.

PAPER’S FINDINGS

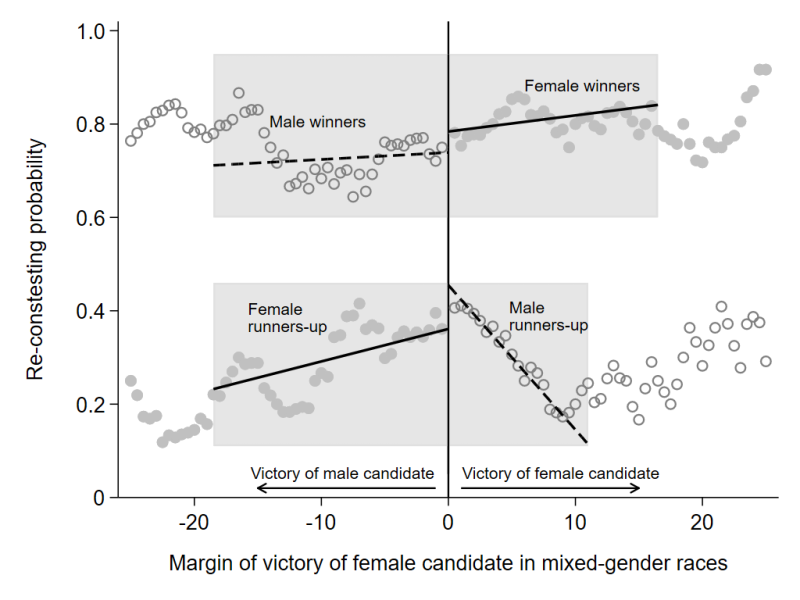

The figure illustrates the re-contesting probability of the top two candidates in mixed-gender races by gender and by vote outcome. The quantities of interest are the values of the four series next to the 0% margin. The figure reveals that female candidates who lose a close election exhibit lower recontesting rates than male runners-up. Conversely, female winners demonstrate equal or greater persistence in political competition than their male counterparts. In summary, our findings suggest that top female candidates are more affected than top male candidates by the outcome of the vote.

We then explore potential mechanisms. First, we show that the difference in political persistence between genders cannot be attributed to systematic differences in characteristics such as past participation in elections, age, occupation, political orientation, or affiliation to a political party. Second, we rule out the possibility of a demand effect, by showing that gender differences in the probability of being elected do not account for the observed structure in re-contesting decisions. Third, we consider gender differences in broader political career choices or aspirations and find that female runners-up who don’t re-contest are not likely to drop out of politics at large, but are more likely to run for lower ranks of municipal lists. Fourth, behavioural explanations involving gender differences in competitiveness may play a significant role. This includes differences in general attitudes towards competition, beliefs about relative performance and risk and feedback aversion. Our analysis supports this mechanism, as we find that the win-loss gender gap is more pronounced among older, more experienced candidates, those in the public sector, left-wing candidates and candidates formally affiliated with a political party—traits that also correlate with attitudes towards competition.

Alternatively, the observation that the win-loss gender gap is mainly driven by candidates formally affiliated with a political party aligns with the notion that political parties may be more inclined to replace a female candidate after a loss. Such a “glass cliff” in fact corresponds to differential preferences or beliefs by political parties regarding male and female candidates. Unfortunately, the data do not allow us to disentangle the role of political parties in nominations from potential differences in female and male candidates’ decisions depending on the election outcome and on adherence to a formally organised political group. Both behaviours might be at play.

SO WHAT?

We undertake a final quantification exercise to assess the relative contribution of cross-gender differences in persistence in explaining women’s under-representation in politics vis-à-vis other channels. We find that it can at best account for onetenth of observed women’s under-representation among office-holders. This finding highlights the prime importance of voters’ discrimination as the most important mechanism behind the low share of women among officeholders for a given intensity of female participation in politics. Still, the two mechanisms together hardly compete with the simple shortage of female candidates that remains the main driver of women’s under-representation in politics.

Observations are candidates who ran in the 2008 and 2014 municipal elections. A 2008 (2014) candidate is considered as re-contesting if she runs again for office in 2014 (2020). The sample is restricted to the best two candidates in each election and to mixed-gender races. Dots represent averages within windows of 2% vote margin moving in 0.5% steps. Lines of sub-figure (a) are locally smoothed series using a 5-dot window. In sub-figure (b), the width of shaded areas indicates gender- and vote outcome-specific optimal bandwidths, and lines are order 1 polynomials fitted using triangular kernel weights. Graphical representation is restricted to the [6 25%, 25%] interval.

Figure. Re-contesting probability of runners-up and winners by gender in mixed-gender races.

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Winter 2023.

© Photo by Pascal Fossier on Adobe Stock