Alen Mulabdic, Lorenzo Rotunno, 2022, European Economic Review, 148 (C)

»

In our gravity estimates, the “border effect” – i.e., the extent to which internal trade exceeds international trade– is significantly larger in government procurement than in private markets, the difference being more pronounced for services.

RESEARCH PROGRAM

Government procurement – i.e., purchases of goods and services by public authorities - is a major market, accounting for about 12% of world GDP in 2018. Given its sheer size, it is no surprise that governments often prefer local over foreign providers to achieve socioeconomic objectives – think of ‘buy national’ clauses. Yet, governments have committed to greater market access in government procurement by joining ‘deep’ preferential trade agreements (PTAs). As shown in Figure 1, PTA provisions in government procurement have become more common since 2000.

Figure 1. Number of PTAs with and without enforceable provisions in government procurement

Against this seemingly contradictory policy landscape (adopting discriminatory measures while liberalizing through PTAs), how ‘national’ is government procurement relative to firms’ purchasing strategies? And have deep PTAs contributed to liberalizing government procurement markets? In this paper, we address these questions by estimating a standard gravity model for cross-border procurement flows. The empirical analysis aims at quantitatively assessing barriers to cross-border government procurement and identifying the role of trade agreements in reducing them.

Recent empirical work on the local bias in public procurement exploits contract-level data often specific to one or a few countries (e.g., the US and EU countries) to identify the determinants of a bias towards local firms in government auctions. We use cross-country input-output tables to construct aggregate measures of cross-border flows in government procurement. Applying the analysis to a cross-country setting allows us to estimate the trade effects of specific provisions in PTAs and to derive theoretically consistent measures of home bias in government procurement.

PAPER’S CONTRIBUTIONS

The two main ingredients of our empirical analysis are a gravity model for government procurement flows and inter-country input-output (ICIO) tables from the OECD TiVA database between 1995 and 2015. The model specifies bilateral flows in public markets as a function of importer and exporter specific characteristics and bilateral trade cost factors, including PTA with specific provisions in government procurement between the two countries. Our empirical definition of government purchases sums the “government expenditure” final demand column and the “Public Administration”, “Health” and “Education” columns of the ICIO tables. Descriptive trends in the data show that (i) the public sector spends considerably more on services than goods compared to the private sector; and (ii) that the import share of expenditure in government procurement relative to that in the rest of the economy is particularly low for services.

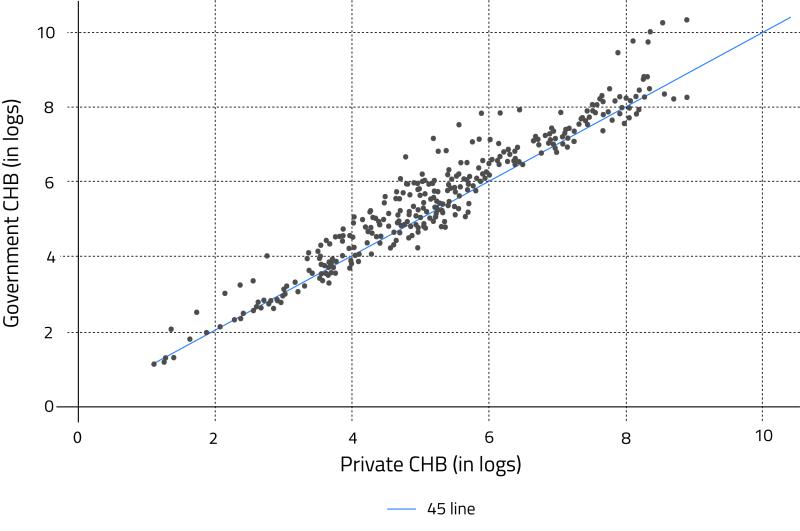

Two sets of findings from the econometric analysis stand out. First, we confirm descriptive and anecdotal evidence of a home bias in government procurement. In our gravity estimates, the “border effect” – i.e., the extent to which internal trade exceeds international trade – is significantly larger in government procurement than in private markets, the difference being more pronounced for services. Using the theoretical framework underlying our empirical model, we also estimate a “Constructed Home Bias” (CHB) index that measures how trade barriers of different types around the world inflate domestic purchases relative to their level in a counterfactual free-trade scenario. We find that the index is higher on average in public than in private markets, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. CHB indexes at the country level

Second, we find that PTAs with specific provisions have a liberalising effect on government procurement, with a larger impact for services than for goods. The effect is driven by ‘unilateral’ provisions – i.e., where it is difficult to exclude firms from countries outside PTAs. Examples of these provisions are the adoption of an e-procurement system and the availability of statistics and information on procurement auctions. Our results have implications for trade negotiations. The findings that national borders are relatively thicker for services and that policy initiatives targeted at government procurement have increased cross-border procurement of services hint at complementarity between negotiations on services trade and cross-border procurement.

FUTURE RESEARCH

This paper is a first attempt to better understand home bias in government procurement. More work is needed in this area, at least along two dimensions. First, preference for local suppliers as estimated in our analysis is a catch-all measure that can be driven by truly protectionist motives and other socioeconomic objectives (e.g., preferential treatment for small and medium-sized suppliers). Collecting data on domestic procurement policies could help identify the different determinants of home bias. Second, because government might favour local firms to boost local economic development, it is important to gauge whether receiving procurement contracts actually improves firms’ performance and local economic conditions.

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Winter 2023.

© PiyawatNandeenoparit / Adobe Stock