Pierre André, Yannick Dupraz, 2023, Journal of Development Economics, Volume 162, May.

»

Educated women married educated men,

and these educated men were more likely to take additional wives.

RESEARCH QUESTION

Polygyny, men marrying several women, is practiced in many parts of the world. It is especially common in Africa, in a region stretching from Senegal to Tanzania, where a third to a half of married women are in polygynous marriages. Polygyny has, however, greatly declined in the last century — one of the most dramatic transformations of marriage practices worldwide.

While less than a third of school-age children attended primary school in Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1950s, about 80% do today. Did this massive educational expansion play a role in the decline of polygyny? To answer this question, we study Cameroon, a Central-African country where primary education boomed in the 1950s. We investigate whether the education the young received during this transformative period influenced their decisions regarding marriage.

What difference could education make regarding polygyny? First, education can change cultural norms. In Africa, during the colonial period, formal education was provided by Christian missions and colonial governments. Christian missions were explicitly opposed to polygyny and promoted monogamous marriage. However, if we look at public, nonreligious education, it appears that public schools did not actively discourage polygyny, though colonial governments also perceived monogamy as a superior marital practice.

Education can also impact polygyny by empowering women, giving them access to greater opportunities for paid employment, and making them less reliant on marriage for financial security. Their increased economic independence could grant them greater bargaining power in deciding who to marry. They might be more likely to choose a monogamous marriage, and be able to prevent their husbands from taking additional wives.

Finally, we need to factor in what economists call “marriage-market returns to education”. If education is valued by potential partners, it will make people more desirable on the marriage market. This could allow men to take more than one wife. More desirable women could have an easier time finding a partner willing to marry monogamously. On the other hand, women (and their families, also involved in marriage decisions) could value both monogamy and husband traits associated with polygyny, like wealth or social status.

Our paper uses a wave of school constructions in Cameroon to identify the effect of nonreligious education on marital practices:, in each village, we compare people of school age when a new school was built to older people.

PAPER’S FINDINGS

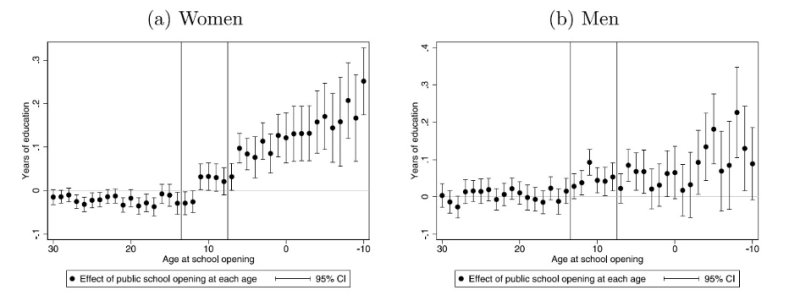

Combining 1976 population census data and administrative data on Cameroonian schools, we know, for all individuals residing in Cameroon in 1976, how many schools there were in their village at their birth and throughout their lives. Using this data, we study how education and marriage practices changed in villages where a lot of schools were built versus villages where few or no schools were built. We regress an individual’s education on the number of school openings at each age, controlling for village and year of birth fixed effects. Figure 1 plots the coefficients of this regression. Schools opening in the village before an individual was 7 (the school entry age) increase years of education, but reassuringly, schools opening after age 13 have no effect.

In a more compact exercise, we regress education and polygyny on the number of private and public schools in the village when a person was of schoolentry age. We find that one extra public school in the village when a woman was a child, increases her education by 0.08 years and her husband’s number of wives by 0.02. Taken together, these figures imply that one year of education increases a woman’s number of co-wives by 0.2. We also find that education increases a man’s number of wives. Looking at women’s marital rank, we find that education increases the chances of being the first wife in a polygynous union, but not of being the second or third wife. In polygynous unions, first wives traditionally have higher status and more bargaining power.

Did going to a public school increase Cameroonian women’s preference for marrying polygynous men? Hard to believe. But men who ended up marrying more than one woman came from wealthier families, and had higher levels of education and better employment prospects. In a period where labor-market opportunities for women were limited, it is not hard to believe that women and their families valued these characteristics. In the paper, we show how assortative matching in education can help explain why secular education made women more likely to marry polygynous men. Educated women married educated men, and these educated men were more likely to take additional wives. Using a structural model of marriage, we show that accounting for assortative matching in education is enough to explain why educated women became the first wives of polygynous men.

Figure 1. Event-Study Graphs: Effect of School Openings on Education

Note: both figures display the coefficients of a regression of an individual’s years of schooling on the number of public and private school

openings in their village at each age, along with village and cohort fixed effects and other controls. Only the coefficients on public school

openings are shown on these graphs, for readability. The regressions for men and women are run separately.

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Summer 2023.

© Photo by Vasily Merkushev on Adobe Stock