Trust in the market declines as the scandals hit the fan, exposing frequent instances of tax evasion and fraud in major companies. Last year alone, more than 400 000 financial crimes were registered in France. With such record abuse, it is becoming difficult for decision-makers to avoid much-needed regulation. Like the new “fiscal policy” launched by the French Ministry of Finance in July 2019, establishing 250 customs officers and fiscal agents. What’s more, the Interior Ministry is setting up an office dedicated to financial crimes within the judicial police1.

Are ethics and markets incompatible?

The economics world is divided on this. For some, the intrinsic nature of the market corrupts ethical norms and morality. It could even reduce the cost of the trade-off between life and money2. The promotion of materialistic values, asymmetric information and increasing competition among individuals in most aspects of life are eroding rules of conduct and moral values. Others take a different view: the main cause is not the market itself, but its defects. For them, there is no evidence that a monopolistic situation would guarantee the protection of moral values. On the contrary, being able to change supplier if the initial supplier does not give satisfaction may make the market more ethically reliable.

But what ethics are we talking about, and are they unique? This question is essential to understanding the relationship between ethics and the free market. From one culture to another, moral rules or social norms change. Think of the Islamic prohibition on receiving interest, and the reverse position in Christianity, where the prohibition of interest has been questioned by Calvinist doctrine since the XVIII century. Ethics are malleable and change with location, creating a fluctuating relationship with the market. This may also lead to moral flexibility.

What’s the evidence?

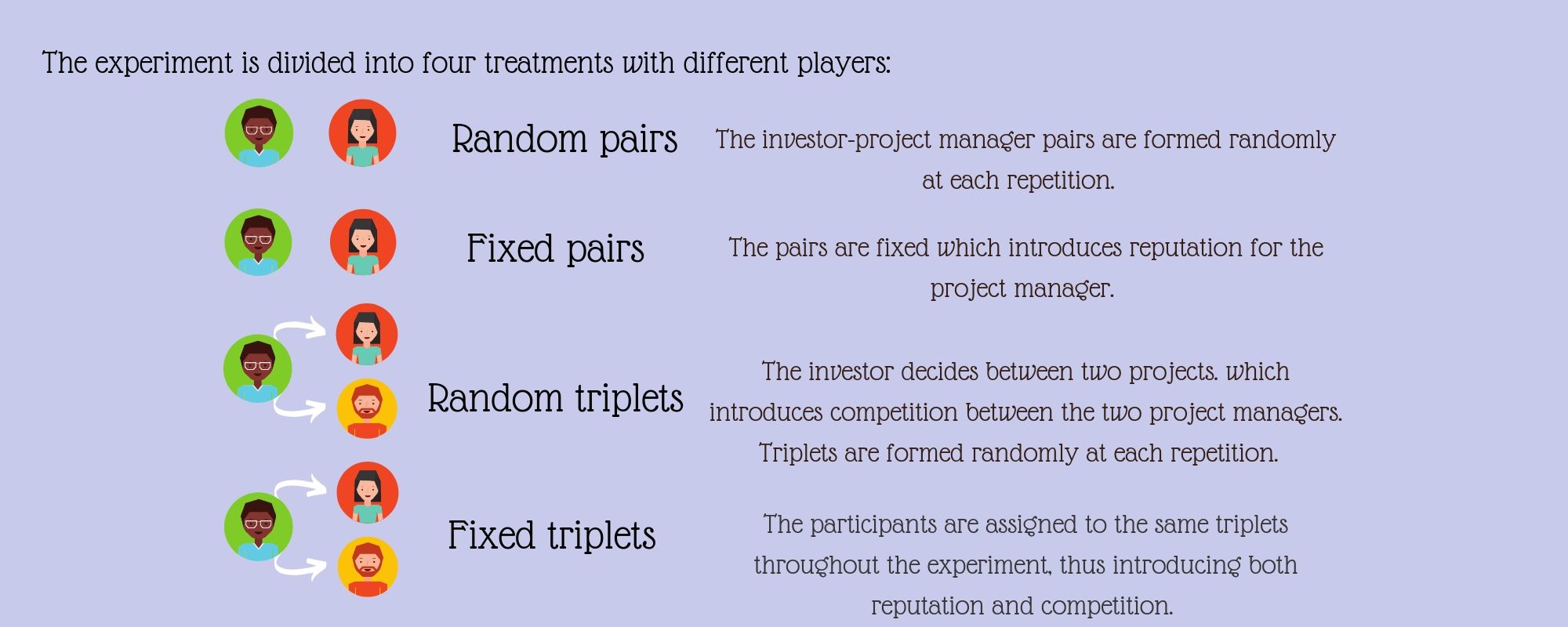

Marie Claire Villeval, economist and research director at CNRS, uses an experimental study to provide an answer. The study, conducted with Chloe Tergiman, Assistant Professor at Penn State University3, looked at individual behaviour by recreating various market conditions. Almost 600 participants were assigned the role of project manager or investor. The investors had to decide on whether to lend money for a project by assessing its quality. The project managers had private information on the values of their projects, but the investors did not. Consequently, the managers could overstate the project’s quality to attract investments.

To reproduce competition in financial markets, some treatments linked one investor to two project managers. The other aspect studied, reputation, gave project managers the opportunity to build their reputation through fixed matching. The goal of this experiment was to assess the impact of market institutions (competition and reputation) on the honesty of individuals.

Pinocchio effect

The result is striking: the great majority of participants lie at least once during the 27 repetitions. Does more competition make a positive change? In the experiment, when the project managers don’t have a competitor, they lie in 50% of cases. But when there is a competitor, the investor has a choice between two proposals, which increases the number of lies to 60%. Competition does not always make the market efficient because false statements increase.

How can this Pinocchio effect be reduced? When pairs or trios are forced to create a permanent relationship, for the fixed treatments, the proportion of lies drops to 30 and 33% respectively. Reputation regulates the negative impact of competition. It limits lies and generates some trust between individuals. Generally, competition increases false statements because it encourages project managers to overstate the quality of their projects, to avoid being replaced by a competitor. On the other hand, reputation reduces lies, even if it cannot eliminate them entirely.

Little lies or big frauds?

On this point, whether in the market or in life, little lies differ from big ones. Some lies are extreme, such as announcing a three-star project when the project is not actually worth one star. By contrast, other lies cannot even be identified because of their subtlety. For instance, presenting two good projects (out of a possible three), when in reality the manager only has one. In this case, the investor can interpret a poor random draw as bad luck. How can reputation and competition influence the nature of lies? To study this, researchers identified four types of lie.

Reputation reduces almost all the extreme lies and the riskier ones. Extreme lies drop from 25% to 1.4% when we introduce reputation (with fixed pairs). The effect does not apply to less risky lies, nor to detectable ones, which together account for more than 40% of cases in all treatments. This is why we can say that reputation does not make people more honest, but changes the type of fraud they practise.

So go ahead and invest?

Investors are not naïve, and they can reduce their investments if they feel cheated. When competition exists without reputation mechanisms, they avoid betting on too-good-to-be-true projects. Competition never increases the number of investments and can sometimes even be discouraging. Reputation, however, increases the number of back-up projects because investors have more faith in the market. In these markets, investors seek reliable information. To ensure the safety of transactions, the reputation factor probably needs to be strengthened by implementing public regulations.

However, there are also other cases where, on the contrary, individuals prefer not to know. This creates a demand for ignorance, and perhaps even markets where ignorance is exchanged. To meet moral conventions, individuals with a choice may choose not to know. In this case, they can ignore the consequences of their decisions, especially the bad ones. At the time they take a decision, they would rather close their eyes to the possible results. This is a recurrent issue in public decision-making. In terms of investments, for instance, it is possible to “not see” the environmental consequences (just as we don’t see the beggar when crossing the road).

While the demand for ignorance can be rationalized and is well-known by economists, we know far less about the supply of ignorance and the existence of ignorance markets. Another experiment conducted by Marie Claire Villeval and authors from the University of Amsterdam4 was based on the conditions that prevail in a market with decision-makers and advisers. Some of the decision-makers chose ignorance rather than risk receiving bad news about the consequences of their self-centred choices. To preserve their ignorance, the decision-makers dismissed any advisers bearing bad news. Because the advisers anticipated this demand for ignorance, they hid information and provided the reality-block expected, a way to avoid unpleasant truths. The competition between advisers had no effect on this demand.

Nevertheless, introducing reputation can strengthen market efficiency. In the first experiment, it postponed the investors’ retreat from the market. They were able to punish the project manager who lied by reallocating their investment to another project. In the second experiment, reputation favoured links between seekers and suppliers of ignorance. It also enabled the decision-makers who favoured transparency to keep the most truthful advisers over time.

“Laissez faire laissez passer”?

This old adage from the French “physiocrats” movement prescribed allowing each individual to act as he liked, using freedom of trade to maximise wealth. At the end of the XX century, Liberal doctrine based on the same principles promoted free trade too. So should we surrender all regulation once we enter the market economy?

Behavioural economics sheds light on this issue by revealing the mechanisms that foster or, on the contrary, discourage ethical acts among individuals. These studies inform public decision-makers and provide keys to limit the market’s dysfunctions and possible abuses. The first experiment underlines the discrepancy between little and big lies and how it is important to provide a different political response to each of the two categories. Reputation also needs to be included in the equation, so that frauds can be detected. An example is compelling major companies to disclose their interests. For the most detectable lies, certainly the majority, other responses may be needed and have yet to be found. The second experiment demonstrates the individual information-seeking strategies at play when the aim is to maintain moral flexibility and limit psychological cost. At a time when fake news abound on the social networks, both those who disseminate information and those who consume it have to take responsibility.

Marie-Claire Villeval and Claire Lapique

Infographic Claire Lapique

Photos © Anita Jankovic on Unsplash, Gianfranco Goria on Flickr

Reference : The Nature of Lies in Financial Markets: the Role of Reputation and Competition, Chloe Tergiman† Marie Claire Villeval, May 28, 2019

- 1. https://www.europe1.fr/societe/bercy-et-beauvau-passent-a-la-vitesse-sup...

- 2. Falk, A. and N. Szech (2013): \Morals and markets," Science, 340, 707{712.

- 3. Chloe Tergiman et Marie Claire Villeval. (2019). How reputation and competition affect the way people lie in markets. Miméo, Penn State University et GATE, Lyon.

- 4. Shaul Shalvi, Ivan Soraperra, Marie Claire Villeval et Joël van der Weele. (2019). Shooting the Messenger? Supply and Demand in a Market for Ignorance Miméo, Université d’Amsterdam et GATE, Lyon.