Nathalie Ferrière, 2024, The World Bank Economic Review, Volume 38, Issue 1, pp. 185-207.

»

Small donors compensate for US policy up to one year,

while large donors tend to mimic the US allocation regardless of the time lag.

RESEARCH QUESTION

In low- and middle-income countries, it has been reported that one in two pregnancies is unwanted. Without underestimating the impact of demand, the availability of family planning (FP) programs is considered to play an important role. In developing countries, FP programs rely heavily on foreign assistance, with international donors contributing approximately 48 percent in 2018. Nonetheless, the availability of funds is not always reliable and is subject to the whims of donors, as well as their capacity to coordinate and compensate for reduced or withdrawn contributions from other donors.

This study investigates how other donors adjust their allocation of family planning aid in response to the United States’ allocation. This question is crucial, considering that the US accounts for approximately 49 percent of family planning disbursements since 1990. However, changing US policies on family planning due to domestic debates surrounding abortion have led to significant variations in their family planning aid. Therefore, the interactions between other donors and the United States will critically affect the ability to mitigate both family planning aid volatility for recipient countries and the adverse consequences of inadequate funding for women.

We exploit the reinstatement of the Mexico City Policy by every Republican president in the US, combined with recipient countries’ likelihood of receiving aid from the US. This policy prohibits funding NGOs involved in any abortion-related activities. It leads to a tremendous decrease in US FP aid during Republican terms.

PAPER’S FINDINGS

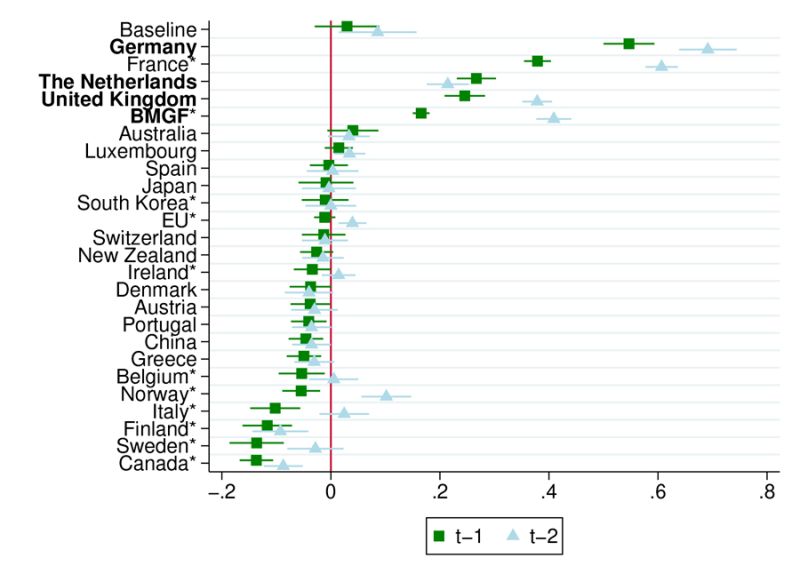

The figure summarizes the main results of the paper. The estimates represent the effect, in percent, of 6US family planning aid allocation in country r, one (green square) or two (blue triangle) years prior, on the family planning aid allocation of donor d in country r at time t. A positive estimate means that a reduction in US aid leads to a reduction in the country’s aid.

1. We find no immediate reactions from other donors, nor any reactions one year later (baseline results). We interpret this as an impact of what other donors call the «decency gap». The public good aspect of providing means for women to choose their reproductive patterns exceeds the political costs and competition effects that generally lead to a positive reaction from other donors.

2. We find reactions after two years. Donors tend to decrease their allocation in line with the United States, with the change in reaction over time being statistically significant. The sector no longer interests public opinion. Thus, the «decency gap» effect is no longer relevant, and competition between donors matters more.

3. We find heterogeneity among donors. Small donors compensate for US policy up to one year later but do not respond to or align with the US allocation after two years. Conversely, large donors, for whom competition with other donors and political autonomy are more important, mimic the US allocation regardless of the time lag. unemployment probability. However, conditioned on being employed, they can be expected to earn higher wages, as they are more likely to receive multiple job offers to choose from.

FUTURE RESEARCH

This study provides new evidence of strategic behavior among donors and opens three future research directions.

First, we need to investigate whether these results found for one specific sector, family planning, and the largest donor, the United States, can be generalized to other donors and sectors. The theoretical literature (Annen and Moers) suggests that if a donor is small, other donors’ reactions could be different. Similarly, a sector with less opposing values may arouse different reactions. This paper provides a clear case of variation in aid that could enable investigation of aid effectiveness at the sectoral level.

Second, future research should address donors’ interaction at the subnational level rather than at the national level. Adjustments could be less costly for donors within countries than between countries. The launch of geocoded data on aid should make this type of analysis possible.

Finally, one stakeholder is still missing from the framework: the domestic government. Domestic governments can also adjust their own spending depending on how much they receive through foreign assistance. To truly understand how best to finance development, we need to include these reactions in the broad framework. This is the objective of our ANR FISCAID project, which starts in January 2025.

Figure: Bilateral Reactions to US Family Planning Aid Allocation (1990–2020)

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Winter 2024.